The Environmental Protection Agency released its first two sets of residential soil test results this month as part of its investigation into rail yard pollution in Houston’s Greater Fifth Ward, finding higher levels of cancer-causing contaminants at 11 locations.

These locations include the community center located at Julia C. Hester House with an Early Headstart preschool, the Boyce-Dorian Park and Dogan Elementary School, as well as eight private residential properties. However, according to the EPA, the levels do not immediately threaten the community.

Despite this, residents have expressed growing frustrations over the results and their community’s history of health issues. These concerns came to a head at a public meeting hosted in Greater Fifth Ward Thursday night.

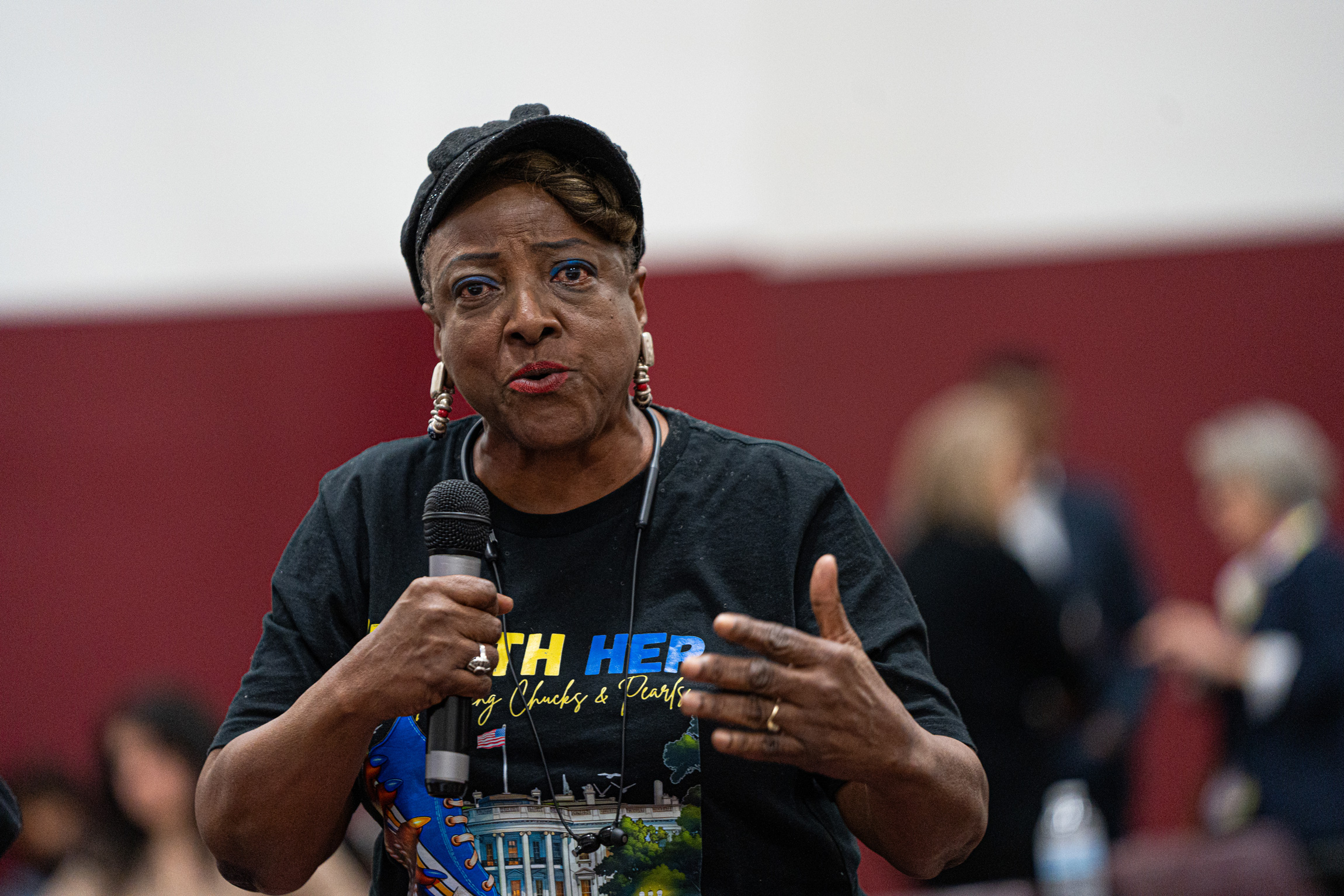

Sandra Edwards, an environmental activist and resident of the neighborhood, stood up and faced the entire crowd at the Carl R. Walker Multipurpose Center, where the meeting was hosted.

“How many of you here are confused?,” Edwards asked. “I’m confused because I don’t understand what (the EPA) just told me. I know it has nothing to do with us dying every day and us losing our lives and our loved ones in Greater Fifth Ward. I want to know how this will help us in the future?”

Union Pacific Railyard, supervised by the EPA, spent months testing private and public properties for soil contamination from the old Southern Pacific railyard off Liberty Road in Greater Fifth Ward. Now completed, the results will be released directly to property owners throughout the spring. The federal agency mailed the results to the six public properties at the end of January and will mail the results for the 26 other properties on Friday.

While the residential results for private properties cannot be publicly released, the agency posted the results for public properties on their website, which included three city parks, two elementary schools and the community center – Julie C. Hester House. EPA and Union Pacific investigators found higher levels of dioxin – a toxic cancerous byproduct of industrial processes and burning waste – at a grassy lawn behind Hester House and next door to an early headstart preschool run by the Gulf Coast Community Services Association.

The EPA dioxin limit for children under 6 years old is 48 parts per trillion, and 500 parts per trillion for adults. The test was at 220 ppt.

“When we see concentrations that are four to five times higher, we quickly realize we need to know more,” said Casey Luckett Snyder, EPA regional project manager. “We need more information on how much dioxin there is, where we are seeing it and at what concentrations are we seeing it at.”

Harris County has since put up a fence around Hester House and the EPA pulled about 48 more soil samples on Wednesday and Thursday this week to investigate further. Luckett Snyder also hosted a private meeting Wednesday night with the parents of children attending Early Headstart to explain the contamination and ongoing action.

As of Thursday night, Gulf Coast Community Services Association has not responded to requests for comment.

In a statement, Union Pacific said “dioxins and other chemicals that were sampled are commonly found in densely populated areas with a history of industrial activity and derive from a large variety of sources.”

“It is premature to identify a source before the entire testing and evaluation process is completed,” the company said.

The tests EPA is taking now will be released in about six to eight weeks. In the meantime, Hester House and Early Headstart will remain open.

An investigation in Greater Fifth Ward

From 1911 to 1984, Southern Pacific Railroad used the hazardous substance creosote to preserve wooden railway ties at the rail yard site in Greater Fifth Ward. The company merged with Union Pacific in 1997.

Creosote is derived from coal and wood. The contaminant – which can contain dioxins – has been shown to cause cancer in the respiratory tract, skin, lungs, pancreas, kidney, central nervous system and other parts of the body. Experts say these creosote chemicals leached underground over time and spread out into the Greater Fifth Ward community, resulting in a contaminated groundwater plume under residential homes just north of the property.

In 2019, the state health department designated the Greater Fifth Ward, Kashmere Gardens and Denver Harbor a cancer cluster for having a higher-than-average level of cancer cases. Following this, Union Pacific, supervised by the EPA, began investigating the contamination.

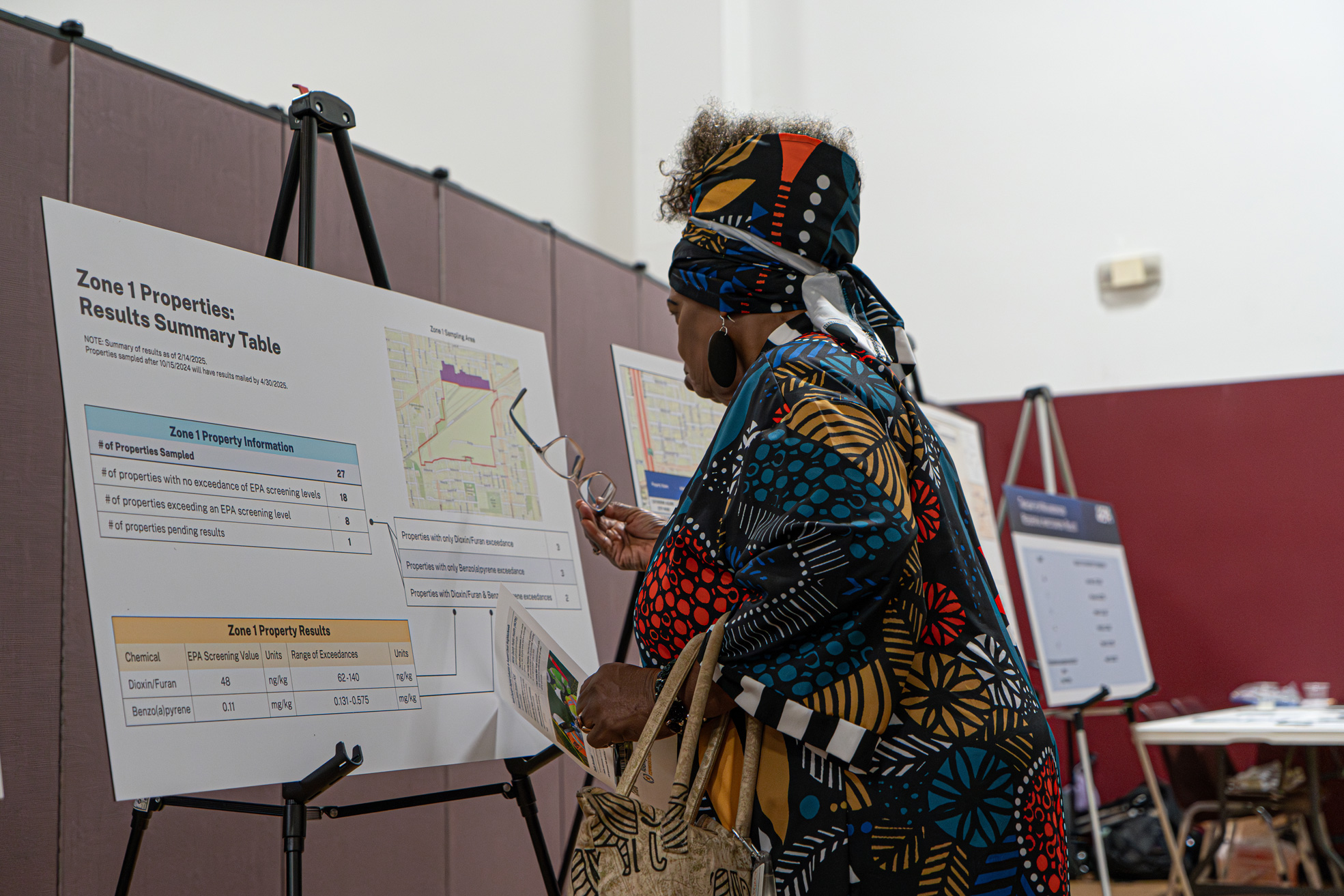

The residential areas near the Union Pacific railyard being tested are split into four zones, divided by location. The results for the first zone – the 26 properties directly north of the railyard – will be mailed Friday. The EPA will release the areas east, west and south of the railyard at the end of March. The rest of the results, which come from properties sampled after October 15 last year, will come out at the end of April.

Once this is completed, the EPA will conduct a health risk assessment that will come out later this year. The risk assessment will take all the results that are above the EPA screening level and determine the cumulative impact the contaminants have on the community.

Investigators did not find contamination that exceeded the EPA screening level at Catharine Adams and Barbara Jordan City Parks. Boyce-Dorian Park and Dogan Elementary School had very low exceedances that don’t warrant immediate action, while Atherton Elementary School will need to be retested due to a conflict in data.

The dioxin exceedance level for children means a child would need to eat and play constantly in the dirt for six years 24 hours 7 days a week for an increased risk of health effects, according to the EPA. The same goes with adults, but for 26 years.

“We use the absolute most conservative number to find a health effect,” said Luckett Snyder. “We ask if a child is sitting out here eating dirt for six years, would it cause health issues?”

At a public meeting Thursday night, Luckett Snyder also went over the 27 residential locations in Zone one tested by Union Pacific and the EPA. 18 locations did not exceed EPA screening levels, while eight did and one location is still pending results. These were locations where residents allowed the EPA and Union Pacific to enter their property and test the entire yard for contamination.

The eight results that exceeded 48 ppt will be added to the overall health risk assessment.

Not enough action

During the public meeting hosted by the EPA, members of the community expressed frustration over the lack of action for all those residents who have lost lives to cancer in Greater Fifth Ward.

Edwards, the environmental activist, is one of many residents who feels this way about the EPA investigation. For years, the contamination from the Southern Pacific railyard leached into the neighborhood. Elderly residents say they remember a toxic smell from their childhood, oil glistening in ditches and floodwater with a chemical sheen.

Today – nearly 50 years after the fact – residents and activists say the contamination will have faded over time, erasing any serious levels of carcinogenic chemicals from the soil.

Pamela Matthews, a longtime resident of Greater Fifth Ward, teared up thinking about her brother, Ronald Gobert, who had recently passed away from cancer. They discovered he had severe stage four cancer in November and he died by January.

Her mother passed away from cancer two years ago and Matthews is in remission from ovarian cancer. At the meeting, the 63-year-old wore a hat saying, “I am here today because God kept me.”

“We lived right by the railyard,” she said. “Right there and we all got sick.”

In response to these concerns, Luckett Snyder said the EPA only “evaluates current environmental conditions” and they “do not test people.”

Even so, Omar Valdez, lead health assessor from the Texas Department of State Health Services, said connecting the contamination with health is difficult.

“The challenging thing is when you detect (the contaminants), they are not indicative of a disease,” Valdez said. “They’re not necessarily indicative of a certain concentration of illness and that’s frustrating to anybody who wants to connect these thoughts. The most meaningful data is what is in the environment today.”

Still, residents pushed back – citing the unfairness of the past and the confusion of the future. Residents began to leave early, frustrated with the process. People hugged on the way out and cried.

Pamela Bonta, an environmental activist in Houston, stood up toward the end of the meeting, calling out that residents in Greater Fifth Ward – with their higher than average cancer rates – are sick for a reason.

“You’re saying the levels are not exceeding so you’re going to be okay,” Bonta said. “Well, I wouldn’t want my child playing at Hester House. I wouldn’t want my child at that daycare.”