Van Nguyen maneuvers through Montrose Nails with a phone tucked between her ear and shoulder and a smile on her lips. Decades of muscle memory guide her hands as she logs the appointment while sharing a laugh with a customer she has known for more than a decade.

Next to Van, her niece drills down another customer’s acrylics, glittery plastic dust catching sunlight through a haze of acetone. Across the room, Van’s sister hums quietly as she lacquers an intricate design on another customer’s nails.

Six days a week for the past 20 years have passed like this for Van and her family in what once was a quiet strip of Houston’s Montrose Boulevard.

“She’s not my mom at the salon,” Van’s daughter, Thu Nguyen, said recently. “She’s the boss lady. My aunts who work with her, they’re sisters. But at the end of the day, at the salon, she’s the boss.”

Van Nguyen left Vietnam after the fall of Saigon – 50 years ago Wednesday – first making her way to a refugee camp in Thailand, and later to the Philippines, where many refugees looking to go to the United States went, awaiting sponsorship.

The end of the Vietnam War also indirectly sparked Vietnamese immigrants’ entry and eventual transformation of the American nail salon business.

Their eventual domination of the nail industry began innocently enough in a northern California refugee camp in 1975, led by an unlikely teacher – actress and activist Tippi Hedren, star of Alfred Hitchcock’s “The Birds” and mother to Melanie Griffith, and grandmother to Dakota Johnson. The story is that during a visit to the Hope Village refugee camp in Wiemar, California, the intricate designs on Hendren’s long nails caught the attention of several of the women there. Soon, Hedren began visiting the camp every weekend with her Beverly Hills manicurist, teaching nail care classes to around 20 women.

Hedren also helped the women find nail salon jobs in Southern California, which now boasts the country’s largest number of Vietnamese immigrants. Their influence radically changed the accessibility of manicures, based in part on the cheaper labor offered by refugees, which allows Vietnamese American salons to charge less than their counterparts.

RELATED: 50 years later, the fall of Saigon still resonates throughout Houston’s Vietnamese diaspora

For refugees with low English proficiency, working on nails offered a low barrier to entry business. After Vietnamese-owned beauty schools began to spring up in California in the 1980s, Vietnamese immigrants’ stake in the industry grew almost exponentially.

Today, 79 percent of American nail industry workers are immigrants and 81 percent are female.

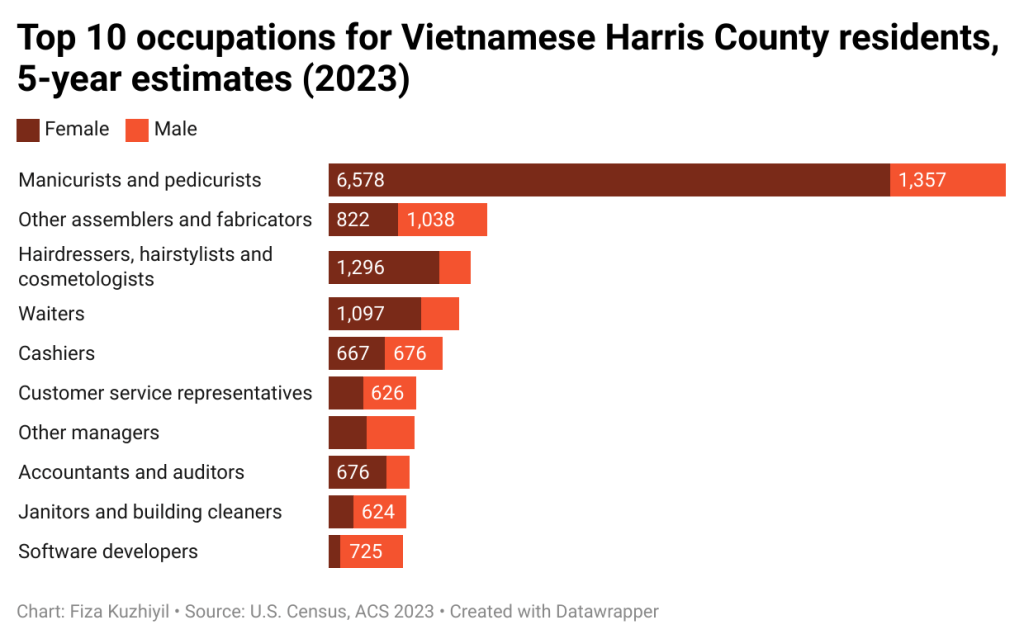

In Houston, home to the second largest Vietnamese population in the country, nail technician is the most popular occupation among Vietnamese workers, according to U.S. Census data.

Arnold Jin, a professor of Asian American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin attributes today’s Vietnamese dominance of the nail industry to how shared language and culture eases entry into the job. In the past 25 years, he said, the Vietnamese migration to Houston mostly consisted of immediate family members sponsoring each other. New immigrants facing underemployment are more likely to go into the industries that employ the family members who sponsored them, Jin siad.

Cultural bonds

Sponsorships allowed immigrants to slip seamlessly into the web of Vietnamese industries at the arrival gate, letting them skip the years of networking otherwise needed to break into business.

Additionally, Jin said, shared traumatic experiences, such as war, build trust, even among strangers. As a result, he said, refugees tend to hire those with similar lived experiences.

An estimated 76 percent of all Texas nail industry workers are of Vietnamese descent, and Harris County ranks among the top 10 counties in the nation with the largest number of nail salon workers. This dominance goes beyond the salon into the entire supply chain, from construction to product supply and beauty schools.

“If everyone around you, if they look like you, if they talk like you and if there’s like a cultural understanding there, then, it makes wanting to work in this particular industry a lot more palpable,” Jin said. “It’s easier to see what a pathway to potentially success might look like.”

A quarter of Texas’ nearly 8,000 licensed salons are in Houston, where more than 40 percent of the state’s licensed manicurists operate, according to Texas Department for Licensing and Regulation data.

EARLIER: Justice proves elusive in son’s search for Houston Viet journalist’s killers 40 years later

The matriarchal nature of Vietnamese culture, Thu said, made watching her mom start and run a salon feel natural. When aunts and cousins joined the business, the salon turned into a family homebase.

Thu Nguyen, now 30, grew up in the salon, where four of the nine current employees are relatives. The other employees also feel like family, she added, noting they worked at the salon and helped watch over her and her sister over the years.

Family-owned businesses are common in ethnic enclave economies like those of Houston’s “Little Saigon” neighborhood.

Nonetheless, more than three fourths of nail salon employees are considered low-wage workers, more than double the national rate of 33 percent for all industries. A recent analysis by Kinder Institute’s Houston Population Research Center at Rice University found Vietnamese Americans are the poorest Asian minority in the city, highlighting economic inequalities in an industry where workers, mostly women, also are exposed to dangerous, potentially cancerous chemicals.

Buffing boundaries

The last of her siblings to come to Houston, Van arrived in the United States on sponsorship to work with family in the restaurant industry. Eventually, she went to community college and then the University of Texas at El Paso to study electrical engineering.

Even with their degrees, however, Van and her husband were only able to gain technician-level jobs, facing the type of underemployment she had been warned about in the refugee camps.

So, they turned to work they saw as a beacon of family and stability: nails.

Van returned to Houston and began building her clientele at her sister-in-law’s Washington Avenue-area salon. Eventually, opened her own shop, bringing her older sisters and some loyal customers with her.

EARLIER: Despite size, Houston’s Vietnamese population lags when it comes to political engagement

Over the decades, the Nguyen family watched Montrose blossom into a coveted neighborhood with new homes and businesses. Along the way, they and their employees found themselves part of a cultural exchange with a more diverse population and customers than they, perhaps, would have encountered in Houston’s Little Saigon neighborhood.

Van sometimes even shares her homemade Vietnamese lunch with clients, delighting them with fish sauce chicken salad or spring rolls, and some clients bring the nail techs food, indulging them with Mexican food or things they wouldn’t try otherwise.

Montrose Nails also serves as a marketplace for goods and services, not unlike traditional gathering places, such as barber shops and places of worship. When a customer mentions a need for a new doctor, lawyer or another service, Van often is ready with a name of someone she met at the salon.

“It’s not just the economy in terms of the nail salon employee people, but it really is an economic hub in other ways that can be unexpected,” Thu said.

Produce and seafood sellers, for example, make regular stops at Montrose Nails and other salons, having picked up Vietnamese words along the way, offering kumquats and dragonfruits or quất và thanh long.

Over the years, Thu has watched the industry grow and change, including her mother’s decision to eliminate some of the most toxic chemicals from her shop. She started out at the salon scrubbing the pedicure chairs, putting down tables and performing simple manicure tasks, such as applying drying spray to customers’ nails. The work also forced her to practice her social skills, both in person and over the phone with customers making appointments.

“It’s hilarious now because now I lead a civil rights organization in (Washington,) D.C. and I have to talk every day publicly to the media,” Ngyugen said.

Though her parents always encouraged her to find her own career outside, Thu obtained a manicurist license and began taking on clients while enrolled at Rice University. After graduation, she went to work for a civil rights nonprofit, but found herself earning less than most nail salon workers.

With her license and Houston’s vast Vietnamese community, Thu said she feels like she has a safety net should she decide to move back to the city full time. Now, when her parents talk about selling the salon after decades of working 60-hour weeks, she doesn’t feel a need to follow in their footsteps. In its place, she said, is a feeling of responsibility to preserve it as a Montrose cultural hub.

“It’s a chosen family,” Nguyen said, “Grandparents, uncles, aunts, now siblings and then the people who I grew up with, they have kids too, so that’s like one one of the coolest aspects of being in each other’s lives. It’s pretty representative of Houston, the kind of people who come into the salon, we meet people of all backgrounds and stories.”