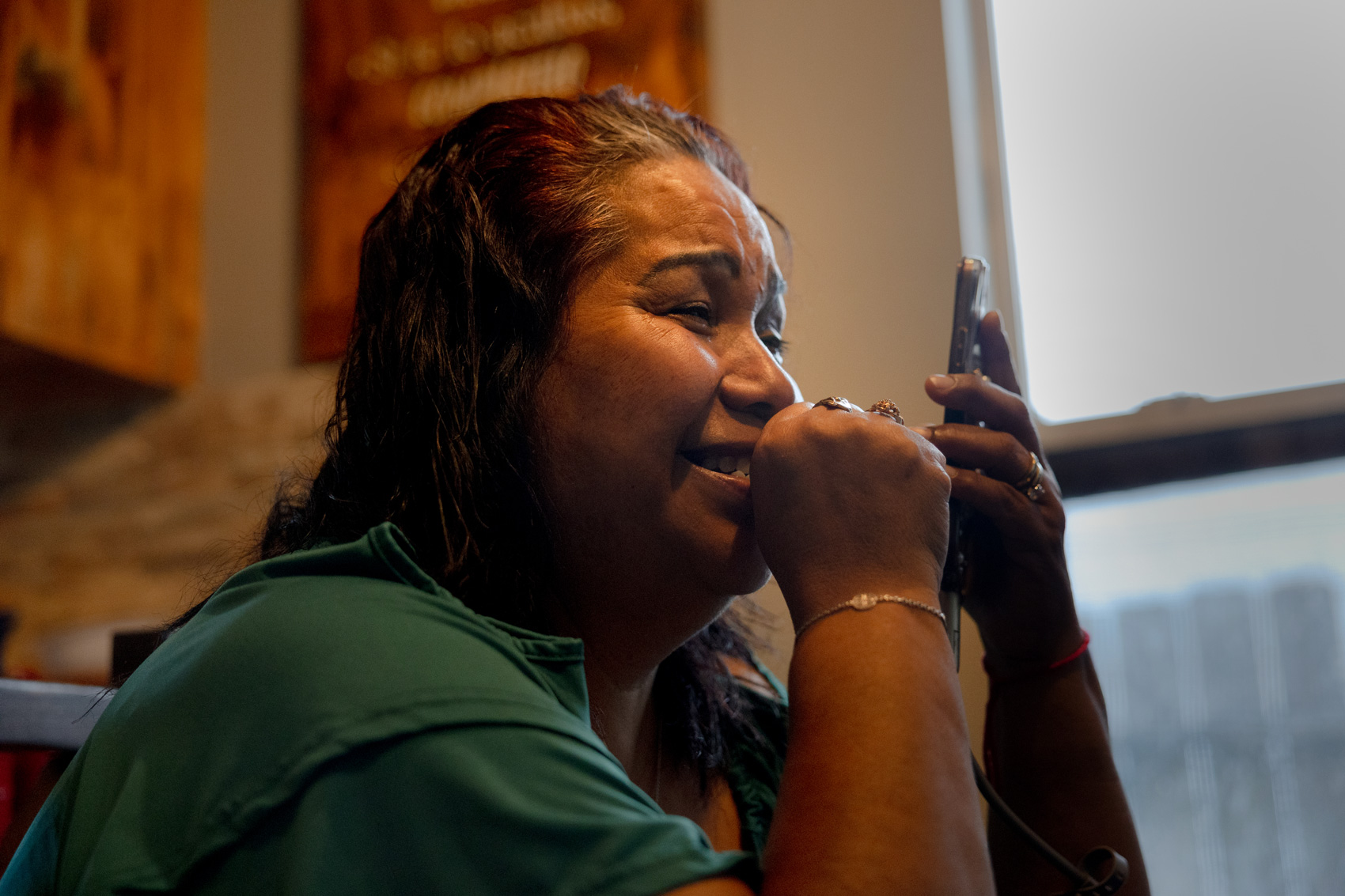

Tears of relief rolled down the cheeks of Alejandrina Morales at 10:25 a.m. on Thursday when she received the news that her husband, Erik Payán, the breadwinner of their household and father who was detained during last month’s major immigration raids in Colony Ridge, had been granted bond by an immigration judge.

“Dios Santo,” “Holy Lord,” she repeatedly said while listening to her lawyer recount the morning’s hearing.

Payán was granted a $5,000 bond by Conroe Immigration Court Judge Mark Evans, an outcome that was initially uncertain for the family. The decision was made after lawyer Silvia Mintz argued Payán’s importance to his family of six, ties to his community, and good character.

It was an amount that the mother, who defended her neighbors and her husband from accusations of criminality and anti-immigrant rhetoric in the wake of the raid on her community, was already at work to cobble together. After hearing about the amount needed, she leaped into action, quickly contacting friends and relatives to achieve her next task: gathering the $5000 needed for her husband’s freedom in time for her daughter’s 25th birthday.

By 2:30 p.m., the family had paid the sum by money order. Yet by 10 p.m. Payán had not been released and Morales and her daughters were still waiting.

Erika Payán, her father’s namesake, hoped to celebrate her birthday tomorrow over tres leches cake with her father, and told the Landing that she was “happy” he could be coming home.

“I still can’t believe that I’m going to see my husband,” Morales told the Landing. “It’s like a dream, a long-awaited dream.

A 10-minute hearing

30 miles away and an hour before Morales received the news, Erik Payán sat in front of the judge at the Montgomery Processing Center. He was dressed in blue sweatpants and sweatshirt uniform, with tan flip flops slipped over socks. A rolled-up piece of white paper sat in his breast pocket.

Behind him, over a dozen tired-looking men hailing from all over Latin America sat watching the proceeding. They waited their turn in similar sweatsuits, colors varying from orange to navy blue. The room was largely quiet, aside from the Judge, lawyers and Spanish language interpreter, as well as the sniffles and coughs from the detained men.

Payán was one of the 118 individuals detained during a major immigration enforcement operation targeting Colony Ridge on Feb. 24, when state police and ICE knocked on businesses’ doors and arrested community members at traffic stops.

Of those detained that day, only two people have been confirmed by ICE to be charged with a crime. Payán was not one of them. The government brought up no past criminal history at his Mar. 20 immigration hearing.

Payán’s hearing, an initial immigration hearing and bond hearing rolled into one, went on for roughly 10 minutes. During the immigration case portion of the hearing, ICE attorney Florince Payen and Payán’s lawyer, Mintz, discussed how the government didn’t know he used a work visa to cross the border in 2004 — which means he’s eligible to adjust his immigration status without having to leave the country.

His next court date was set for Apr. 2 at 1 p.m.

Mintz told the Landing by phone that she takes issue with those that say immigrants should ‘go to the back of the line,” as there are few ways to migrate to the United States legally.

“The issue is that a lot of people that were detained in Colony Ridge are people like Erik, who are hard-working individuals who shouldn’t be detained,” she said.

During the bond portion of the hearing, the judge listed facts about Payán’s life which were submitted as part of his bond application: The fact that he had been in the United States for over 20 years, that he has a child with DACA, a 19-year-old citizen daughter, and that his daughters and grandchild are battling serious illnesses. Judge Evans noted that he had a pastor sponsor who would make sure Payán attended any future immigration hearings. Payán responded to most questions with a simple affirmative.

Did he own his tire shop? “Yes,” said Payán. Did he own his house? “Yes,” he replied in Spanish, relying on a translator as he sniffed — apparently sick.

“He’s not a flight risk,” said his lawyer, Silvia Mintz, from a square on the TV screen to the right of the judge. “He has ties to the community. He’s a hardworking man who takes care of family.”

Judge Evans noted that there may be a way to change Payán’s legal status, and to apply for cancellation of his removal order. He ended up granting the bond $3,000 lower than the $8,000 asked by the government. It was among the lowest bond amounts the judge gave on Thursday.

“Good luck!,” the judge said as he sent Payán back to the waiting area of the Montgomery Facility.

When Mintz met Payán at the facility in the weeks prior, she said his sole concern was not being deported because of his sick children. But Payán told a Landing reporter over the phone on Thursday that he was relieved, as he updated his family on the day’s action.

“I feel good. I was hoping for this but you never know,” he said in Spanish. “I hope to get out today or tomorrow.”

The long wait

By around 4 p.m., back at the Payán home, Morales walked into the living room, with newly-laid lashes, makeup, and shiny pink lipstick – her hair coiffed and parted to the side.

As she stood on the corner of the kitchen table, family members gathered around her, arms touching. Morales passed from child to child, french-braiding one girl’s hair, and brushing and smoothing the ponytail of her granddaughter, Kiomy.

Around them, photos of the Payán wedding, the Virgin Mary and other religious iconography adorned the walls.

She laughed as her daughter Alondra Payán spritzed sparkles on her face and hair in preparation for her father’s return, and cooked the pork rind recipe that she meant to make for her husband the day he was taken by ICE.

At 8 p.m., the family was still waiting for news of Payán’s release. The women snuggled under blankets on the sofa while watching Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. Erika Payán watched from the kitchen table as she crocheted a blanket.

As the clock ticked on, Morales dozed off, wrapped in her blanket.

Suddenly, the phone rang: it was Erik Payán, asking why he hadn’t been released, and pointing out that he was still waiting along with four other people for their names to be called.

The family shifted in their seats restlessly.

“Wait,” Morales urged, “because supposedly they’ll do a count at nine at night.”

Shortly after, the volunteer from the immigration non-profit CRECEN waiting outside the detention center, informed Morales that there was still a lineup of cars waiting for other people to be released.

The uncertainty did little to calm the rising anxiety, and Morales and her daughters started to discuss whether he would even arrive today at all.

As nine came and went, they were no closer to knowing when their loved one would be home.