|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

At first, Ben Wolff could hardly make sense of what he was reading. A man showing signs of mental illness had been sentenced to death. Later found to be psychotic, he was still in prison and the state of Texas seemed to have forgotten all about him – even though he’d had litigation pending in the courts for nearly 30 years.

As the director of the state Office of Capital and Forensic Writs in Austin, Wolff supervises public representation of death row inmates in post-conviction legal proceedings. He keeps a close eye on activity at the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals – which is how Syed Rabbani’s case caught his eye.

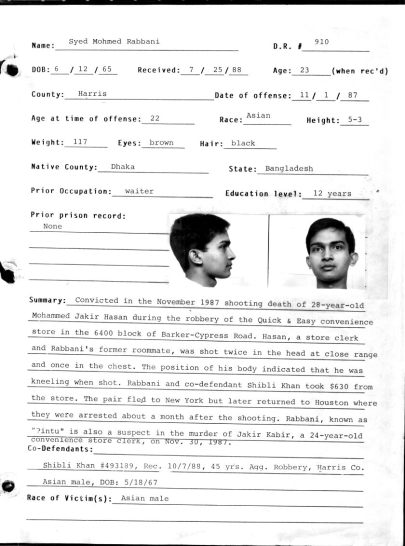

Rabbani, a Bangladeshi immigrant, was convicted of capital murder in Harris County in 1988. Incarcerated under a death sentence ever since, he challenged his punishment as unconstitutional in a court filing. The Harris County District Clerk’s Office identified the filing as pending and sent it up the chain to the Court of Criminal Appeals in 2022, when Wolff saw it.

There was just one problem. The challenge had been filed in 1994 – and nobody, it seemed, had taken action to resolve it ever since.

Moreover, within months of submitting his challenge in 1994, Rabbani had been declared incompetent to face execution by what is now the Harris Center for Mental Health and Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, which provides mental health services in Harris County.

Put simply, Rabbani was mentally ill, a fact that became increasingly obvious in his correspondence over the years.

“I never told you that I’m CIA and diplomat from Bangladesh,” Rabbani wrote to his trial judge, Doug Shaver. That was in 1993. By 1999, he was advising Shaver to contact the CIA for “good living forever drug,” and in a subsequent letter wrote simply, “KARATE RED BELT DUN 10.”

Wolff also discovered Rabbani’s attorney had died in 2008. When the court finally replaced him in 2010, the judges chose a successor who lacked the qualifications to represent death penalty clients.

That attorney, the case record showed, had neither made an appearance nor taken action in Rabbani’s case in 12 years. It wasn’t clear to Wolff whether the attorney even knew Rabbani was her client.

Within months of learning about Rabbani’s case, Wolff submitted a brief to the Court of Criminal Appeals, advising the judges how to handle the legal challenge Rabbani filed all those years ago.

“Mr. Rabbani’s (challenge) should not be decided by this court at this juncture because he is unrepresented,” Wolff wrote. Instead, he recommended the court send the challenge back to Harris County, where a new, qualified attorney would take over Rabbani’s case.

The Court of Criminal Appeals complied. The court appointed Wolff as Rabbani’s new lawyer, and in April 2023 asked Harris County to assess Rabbani’s 1994 filing.

In it, Rabbani’s lawyer at the time explained that the jury in his client’s trial was not permitted to take important factors into consideration when deciding his punishment – factors like a psychological evaluation that found him empathetic and suggestible, and bizarre statements he’d made on the stand.

That, the attorney argued, was unconstitutional.

Now, nearly 30 years later, the Harris County District Attorney’s Office says it agrees.

In a filing submitted to district court in May, the district attorney’s office recommended that Rabbani be granted a new sentencing hearing with a jury that can take those factors, and others, into consideration.

“The facts of this case are just disturbing, procedurally,” said Joshua Reiss, chief of the Post-Conviction Writ Division of the Harris County District Attorney’s Office. “He fell through the cracks.”

For Rabbani, whose mental health problems persist at the age of 57, the stakes couldn’t be higher. A new sentencing trial could mean relief from death row. Moreover, Rabbani could become eligible for parole.

“I’m on death row,” he wrote to his trial judge in 1993. “Life on death row is terrible. I’m suffering.”

Rabbani has waited for a response for 30 years. Finally, he may get one.

‘Egregiously harmed’

Syed Rabbani first came to the United States from his native Bangladesh in 1984 when he was just 19 years old. Three years later, police arrested him for the murder of Mohammed Jakir Hasan, another Bangladeshi immigrant who worked as a clerk at a Quick-n-Easy convenience store. On Nov. 1, 1987, a friend found Hasan’s body curled up in the fetal position in a pool of blood on the floor of the Quick-n-Easy bathroom. He had been shot three times, the medical examiner later found – twice through the head and once in the chest.

Syed Rabbani timeline:

1988 – Rabbani is convicted of the 1987 murder of Mohammed Jakir Hasan and sentenced to death in Harris County’s 262nd District Court.

1992 – The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals affirms Rabbani’s conviction and sentence on direct appeal.

July 1994 – Rabbani’s attorney files a writ of habeas corpus.

September 1994 – Rabbani is found “incompetent to face punishment” by the Mental Health Retardation Authority of Harris County. No further action is taken to resolve his writ.

August 2022 – The Harris County District Clerk’s Office sends Rabbani’s writ to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals.

April 2023 – The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals remands Rabbani’s writ to Harris County for resolution.

May-June 2023 – The Harris County District Attorney’s Office files its recommendation for relief. The recommendation is sent to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals.

Police targeted Rabbani and a friend, Shibli Khan, after an acquaintance told them the pair had confessed to the killing. Though Rabbani maintained his innocence throughout the trial, a jury convicted him of the murder and sentenced him to death in 1988.

However, during the sentencing process, the jury was not allowed to take certain details from the trial into account – things like the baffling statement Rabbani had made about Khan on the stand, a statement that suggested he could be mentally ill.

“When Shibli start dancing, I start dancing with him too,” he told the jury, “because he was Saturn and I was influenced by him.”

This statement, among others, would have constituted “mitigation evidence” – potential reasons the defendant in a death penalty trial should not receive a death sentence.

But juries can only consider mitigation in sentencing when instructed to do so by the court. In Rabbani’s trial, they weren’t – which was entirely legal at the time. Only later, after the U. S. Supreme Court rulings Penry v. Lynaugh (1989) and Penry v. Johnson (2001), did the rules change.

Now, juries in death penalty trials must take mitigation into consideration. Moreover, individuals sentenced to death prior to the Penry rulings can use those decisions to challenge their sentences, giving this argument its legal name – a Penry claim.

Rabbani’s representatives and the district attorney’s office now agree with the Penry claim Rabbani’s attorney made in 1994. Rabbani, the district attorney’s office argued in its filing last month, was “egregiously harmed” by a sentencing process that did not consider multiple mitigating factors presented at trial – including his statement about Khan.

Joshua Reiss, the assistant district attorney division chief, supervised the county’s review of Rabbani’s Penry claim. When Wolff first contacted him about it, Reiss said he was horrified.

“If we think that a conviction is righteous, we’re going to fight like hell to defend it,” he said. “But we’re also going to fight like hell if we think that someone’s not getting the due process they’re due.”

That, Reiss says, is the case for Rabbani, whose constitutional rights were violated in the sentencing phase of his trial.

Though Rabbani has repeatedly maintained his innocence in Hasan’s murder, Reiss emphasized that his guilt is not in question.

“These were serious, heinous offenses for which he is unquestionably guilty,” said Reiss. “That’s not the issue. This issue is, did he get the jury instruction he deserved? The answer to that is no.”

‘You can’t ignore my plea’

In an interview, Wolff declined to comment on why Rabbani’s Penry claim was allowed to languish for so long. However, in his recommendation to the Court of Criminal Appeals, he noted that “lost and found” legal challenges are “a subject of growing concern” in Harris County.

Of particular concern are challenges like Rabbani’s, habeas applications that dispute unlawful incarceration. Wolff quoted Judge David Newell’s dissenting opinion in a prior case: “The Harris County District Court has informed us (informally) that there are an unspecific, but significant number of habeas applications in Harris County that have been delayed for several years, sometimes… even for decades.”

Reiss said the district attorney’s office had no responsibility to resolve Rabbani’s legal challenge in the absence of efforts by Rabbani’s attorneys and the court.

Instead, Reiss said, Rabbani’s previous attorneys and the district court should have acted far sooner.

“There should have been an effort before the trial court to argue, ‘We have a valid Penry claim,’” Reiss said. “And, ‘You need to make a recommendation one way or the other on the merits of this claim.’ And that did not occur.”

The court, meanwhile, “has control over its own docket,” Reiss said. “Any court has the right to order the parties before it to resolve legal issues that have been raised. This case is no exception.”

Judge Lori Chambers Gray, in whose court Rabbani’s legal challenge was filed, declined to comment on a pending case.

In the meantime, Rabbani remains incarcerated in Huntsville, in a prison unit with a hospital facility for inmates with long-term medical issues. He’s been there since at least 1993, when he penned the first of his plaintive, incoherent letters.

“If you don’t get me out CIA will indict you as KGB agent,” he wrote to Judge Doug Shaver. “God talks to me all the time. You can’t ignore my plea.”

Shaver did ignore Rabbani’s plea. In fact, he set an execution date the day after he received Rabbani’s letter.

Because that date was later suspended so Rabbani could proceed with his legal challenges, then eliminated altogether due to his incompetency, Rabbani has remained in legal limbo. For decades, his plea languished in the courts. For years, he was without representation. All the while, his mental health issues mounted.

“Still I am not guilty,” he told the judge at his sentencing hearing in 1988, and asked that his execution be carried out within two months. “I don’t want to spend years on the death row,” he said.